(4 and a half stars)

“Taarikh pe taarikh aur taarikh pe taarikh…”

If you have notions of courtroom proceedings which sound like Sunny Deol screaming these lines and arguing a case with insane hysterics and flourish, then quickly head for a realistic yet more entertaining courtroom drama presented with a mere stationary camera and a liberal dose of vernacular humour.

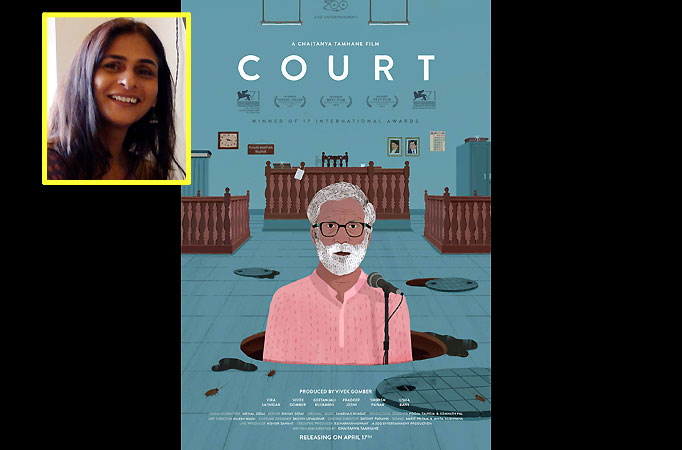

The multilingual film, (English, Hindi, Gujarati, primarily in Marathi) Court, has made history before its debut in Indian theatres. The film has won 18 awards across festivals including a recent National Film award in India.

27-year-old Chaitanya Tamhane’s debut marks the success of Independent filmmaking. Tamhane started his career with a television serial for Balaji Telefilms and moved on to documentary and a short film before making Court.

The film comes at a relevant time when there has been much debate over Marathi cinema getting prime time screening. No doubt, there has been a spate of best films emerging from here, namely; Shwaas, Harishchandrachi Factory and Fandry.

Court revolves around a song, which is supposed to have driven someone not up the wall but down the manhole. The Marathi lyrics are loosely translated thus….. “Manhole workers, we should all commit suicide by suffocating inside the gutters.”

65 year old Dalit folk singer and activist, Narayan Kamble (Vira Sathidar, excellent), is arrested all of a sudden after a stage performance in a local Mumbai suburb. Through a lengthy charge in English, read out in a flat tone and heavy Marathi accent, by a public prosecutor (Geetanjali Kulkarni); we come to know the details. In a very matter of fact tone, it’s suggested that Kamble has incited a sewerage worker to commit suicide through his inflammatory song.

Kamble’s defence lawyer, Vinay Vora (Vivek Gomber, theatre actor and producer) seems to be the only regular English speaking man who sees the bizarreness of it all.

The judge, Sadavarte (Pradeep Joshi), calmly presides amidst dusty old files, in the Lower Court and dictates his conclusions every time to his secretary who types it out on a huge, dated desktop. The proceedings are slower than a passenger train. Kulkarni and Vora speak in turns, without much argument with each other. Witnesses are brought in over weeks and months. The judge gently reprimands a cop for not doing his job. It is understood and accepted that the negligence adds to many months of the accused’s life in jail.

No one questions and no one cares.

The film captures this complacency and the misuse of obsolete laws, with remarkable objectivity. There is only one quiet, emotional scene. Vora sits on the edge of his bed, dressed in a banyan. We just see his back tremble and hear him sob in frustration after a particular, humiliating incident. The cause is more absurd than the charges laid on Kamble.

As the personal lives of all three-the judge, the lawyer and the prosecutors, unfold; the case gets more ridiculous than ever. There are observations regarding the judiciary’s archaic systems, which make a huge comment. In one instance, a lady is not allowed inside the witness box on the grounds of not being “modest” and sober” as she is wearing a sleeveless top.

The scenes outside the courtroom, include extremely natural, daily conversations which keep the tone light, yet add depth. There is gradual revelation of amazing facts, one of which includes a cockroach in a gutter.

Every scene is shot in the same manner: long, stationary one takes and wide angle frames. A great production design adds wonderful texture to locales used. Mostly, there are non-actors who look and behave the part. One of them is Usha Bane, who plays the dead sewer’s wife. She is believed to have suffered the same in real life.

This film could easily be mistaken for a documentary.

The director takes his own time to begin and end every scene. Even the fade-outs last more than a few seconds. This leisurely pace makes you get into the deceptively mundane mood of the prime location and subject: the courtroom.

When Court ends, the last shot is perfect in its irrelevance. And that’s a scary and powerful ‘wake-up” call. All over a song.

(The writer tries to make peace with her own filmmaking nightmares, of being a scriptwriter, actor and assisting film icons by moonlighting as a film journalist.http://gayatrigauri.blogspot.in)

Add new comment